As I approached the Flemington roundabouts Friday afternoon, most of the sky turned an ominous charcoal gray - except for one patch blue as teacups. Rain drenched my path but it didn't matter. The passenger side window was open and the air fresh; it was a pleasure to drive the last few miles to Daria's and Tyler's house. Just before I parked in the driveway, the sky opened. Tyler, the house's sole occupant after everyone else left for Cape Cod days before, loaded dishes into the dishwasher as I stood in the kitchen and shook myself like a sheepdog. About a minute later, a sound like dozens of carpenters attacking the roof with icepicks drove us to the windows, where we saw hailstones the size of marbles knocking over lawn furniture up and down the block. We elected to stay indoors and avoid brain damage. After ten minutes, the hail passed but rain fell in sheets. Getting our two persons and Tyler's two bags into my Grand Am ended with both of us completely soaked. I could only laugh until we drove through the neighborhoods between us and the highway and surveyed the storm damage.

It's worth noting that no two people in my family may be as different as Tyler and I are. He was a Marine. I am a tree-hugging pinko. He believes in traditional family roles. I avoid traditional families until after happy hour. He works in insurance. I work

for insurance. He is an Ann Coulter fan. My politics are to the left of Gandhi's. By the time we crossed the Bourne Bridge onto Cape Cod, he was lecturing about how the unions destroyed American car manufacturing and I was saying the words

bullshit and

overcompensated management fuckpigs with fervor and frequency. For now, that's hours into the future and hundreds of miles away. As we drove up Routes 206, then 287, then 87, then 287 again, the rain and trucks blinded us, and somewhere along the way, we missed seeing the entire Tappan Zee Bridge.

I don't know if you've seen the Tappan Zee Bridge but it's on the biggish side. If someone had misplaced it or left it in his other pants, we were pretty sure we would have heard but neither of us had. Thus, as we were lost in New York State past the section of highway pictured in the MapQuest directions to someplace I've been going my entire life, we both thought back to that place near Mahwah, New Jersey where suddenly the road divided and because the weather reduced visibility to a few dozen feet, we'd had no idea why. By then it was too late, and New York State, with its exits more than ten miles apart, was holding us hostage.

The rain cleared slowly as we continued northward and we took the next exit, where we found ourselves in Outlet Mall Hell. Tyler followed signs for an information booth we never saw. We both looked at the printed directions and came to the same conclusion: we had no idea where we were.

Tata: Scout's honor: I will never again leave for a long trip again with the blessing of Rand McNally. You know, when Paulie Gonzalez was a repo man they had laptops that had detailed satellite maps.

Tyler: I have that and left it on my desk.

Tata: I guess your car has GPS, yes?

Tyler: No. I didn't think I'd need it.

Tata: Look, you couldn't have known we'd see hailstones the size of marbles and houses dropping on my sisters. This isn't your fault.

Tyler: We're stopping at the New York State Welcome Center and reading their maps.

Tata: Well, okay, but then we have to stop somewhere for coffee. This might take awhile.

Proof that my manicure survived this terrible ordeal.

Proof that my manicure survived this terrible ordeal.Staring at the wall map, we chose a route. Actually, I chose a route back to 95 and Tyler said, "Okay, but I still think we should take 84 to Boston and head south." I don't know why he let me have my way. We turned right at Danbury and headed southeast for the coastal cities. I was never so pleased to see New Haven in my life. Actually, I'd never been pleased to see New Haven. An hour and a half later than we should have seen it there it was, and it was pleasing indeed. In the meantime, we learned something about New York State: signs on highways that tell you Dunkin' Donuts are in every inbred, backwoods town are

lying.We stopped where the town consisted of a strip - maybe ten crumbling businesses and some equally ramshackle houses, then - nothing. We looked at each other and tried not to hear the mental banjo music. Tyler turned the car around and we got back on the highway, a little nervous. After that, every exit had a Dunkin' Donuts sign. It was like each town thereafter was poking us in the eye with a caffeinated stick. Once we crossed the border into Connecticut, we were driving out in the middle of nowhere and nothing and there it was: a gleaming Dunkin' Donuts along the roadside.

Tata: Jesus Christ, it's Dunkin' Donuts!

Tyler: Are we stopping?

Tata: Damn right, we're stopping.

Tyler beached the car. We unbuckled our seat belts wearily. "Let us console ourselves with melted cheese," I said. Until this point, our road provisions consisted of Vitamin Water and snap peas. Next thing you know we're scarfing down Denver omelet croissants with sausage and bacon, and if we could have wedged another artery-clogging dietary disaster onto the bread we would have.

These are steamers we did not dig ourselves. Usually, someone in the family goes clamming and everyone eats. There wasn't time Saturday morning. Mom picked these up at a local guy's shop. Grandpa wanted to know who did the clamming and where but Mom didn't know.

Mom steams the clams with broth, pours broth into individual cups and melts butter in custard cups. You eat the steamers by prying open the shells, peeling off the sock as you peel the clam from the shell, dunk the clam into broth to swish free the sand, then dip it in butter. You're supposed to drink the broth, too. Then you are very happy and it is worth a seven-hour car ride during which you say to your sometimes unforgiving brother-in-law, "If I told you this story you wouldn't believe it, would you?" and he says, "No."

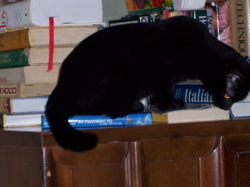

Topaz, lovely Topaz, my dear little bear, has a pet peeve: things should not be on top of other things. Still, madame is not unreasonable and has come around to the possible necessity of the cookbooks remaining atop the buffet. The objet to which she objects is a screw from I know not where, which makes me nervous. I keep finding them but that's not really true, is it? Topaz plainly finds them first. So I am the Christopher Columbus of pre-found screws, and do turkeys get seasick?

Topaz, lovely Topaz, my dear little bear, has a pet peeve: things should not be on top of other things. Still, madame is not unreasonable and has come around to the possible necessity of the cookbooks remaining atop the buffet. The objet to which she objects is a screw from I know not where, which makes me nervous. I keep finding them but that's not really true, is it? Topaz plainly finds them first. So I am the Christopher Columbus of pre-found screws, and do turkeys get seasick? In recent weeks, the kittens have become more definitely teenage. The evidence for this is that they seem to be flying past my head quite often and since kittens as a group seldom develop wings I accept that they are leaping prodigiously. While Drusy is no slouch, Topaz's favorite living room perch is atop my bicycle seat, staring at me - unless Pete's taller bike is parked next to mine. In that case, my seat is no longer gloriously elevated above all perch-worthy surfaces and will not do! Last night, Pete and I were talking and there was a sudden WHOOSH! Out of the corners of our eyes, we saw the tiny kitten leap panther-like. In a blink, the sweet little nutcase magically transformed into the giant jungle cat. The bicycle wiggled for a moment, then became still. The expression on Topaz's delicate furry face reminded us we were made of meat.

In recent weeks, the kittens have become more definitely teenage. The evidence for this is that they seem to be flying past my head quite often and since kittens as a group seldom develop wings I accept that they are leaping prodigiously. While Drusy is no slouch, Topaz's favorite living room perch is atop my bicycle seat, staring at me - unless Pete's taller bike is parked next to mine. In that case, my seat is no longer gloriously elevated above all perch-worthy surfaces and will not do! Last night, Pete and I were talking and there was a sudden WHOOSH! Out of the corners of our eyes, we saw the tiny kitten leap panther-like. In a blink, the sweet little nutcase magically transformed into the giant jungle cat. The bicycle wiggled for a moment, then became still. The expression on Topaz's delicate furry face reminded us we were made of meat. For her part, Drusy is an enthusiastic cheerleader. The kittens follow me everywhere, as kittens will. When I stand in the kitchen, I hear a small whoosh! as Drusy leaps to the windowsill, crosses the radiator and bounds to the top of the washing machine in an instant. I turn around and we are face to face. Miss likes to kiss, so we do. When I turn back to the sink, ingenious Topaz will be standing on the counter, hoping for yummy fish, on her way to sitting on top of the coffee machine, the highest point in the kitchen on which a cat might perch and issue demands, so she does. Drusy, on the other hand, is very easy to love.

For her part, Drusy is an enthusiastic cheerleader. The kittens follow me everywhere, as kittens will. When I stand in the kitchen, I hear a small whoosh! as Drusy leaps to the windowsill, crosses the radiator and bounds to the top of the washing machine in an instant. I turn around and we are face to face. Miss likes to kiss, so we do. When I turn back to the sink, ingenious Topaz will be standing on the counter, hoping for yummy fish, on her way to sitting on top of the coffee machine, the highest point in the kitchen on which a cat might perch and issue demands, so she does. Drusy, on the other hand, is very easy to love.